Commission Exhibit 2011 has been the subject of ongoing debate within the JFK research community. This seemingly straightforward FBI memorandum, compiled at the request of the Warren Commission, was intended to document the chain of custody for several critical items of evidence in the Kennedy assassination. However, it has sparked decades of controversy and confusion—particularly over its connection to CE399, the infamous “magic bullet.”

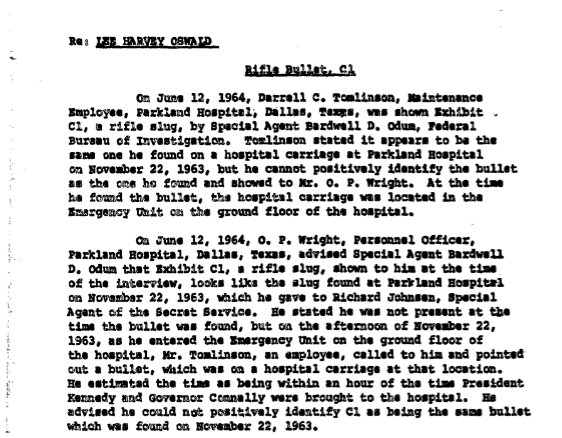

At the heart of this controversy lies the role of FBI Special Agent Bardwell Odum, who, according to CE2011, displayed CE399 to Darrell Tomlinson and O.P. Wright on June 12, 1964. The memorandum notes that neither man could positively identify the bullet as the one they discovered, though Tomlinson reportedly stated it “appears to be the same one,” and Wright said it “looks like the slug found at Parkland Hospital.”[1]

In 2002, researchers Josiah Thompson and Dr. Gary Aguilar interviewed Odum about this alleged event. To their surprise, Odum categorically denied ever handling CE399 or conducting the interviews reported in CE2011:

Again, Mr. Odum said that he had never had any bullet related to the Kennedy assassination in his possession, whether during the FBI’s investigation in 1964 or at any other time. Asked whether he might have forgotten the episode, Mr. Odum remarked that he doubted he would have ever forgotten investigating so important a piece of evidence. But even if he had done the work, and later forgotten about it, he said he would certainly have turned in a “302” report covering something that important.[2]

Odum doubted that he would have forgotten handling CE399, but stated that if he did forget, he would have certainly turned in a 302 report. This is an important point: there are no 302 reports for any of the dozens of interviews described in CE2011. Why not?

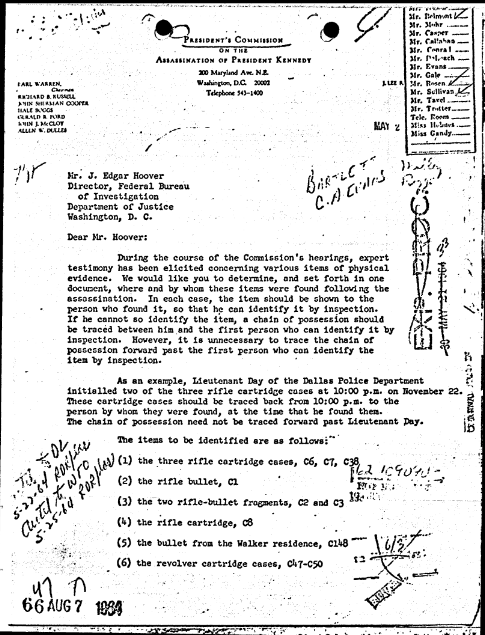

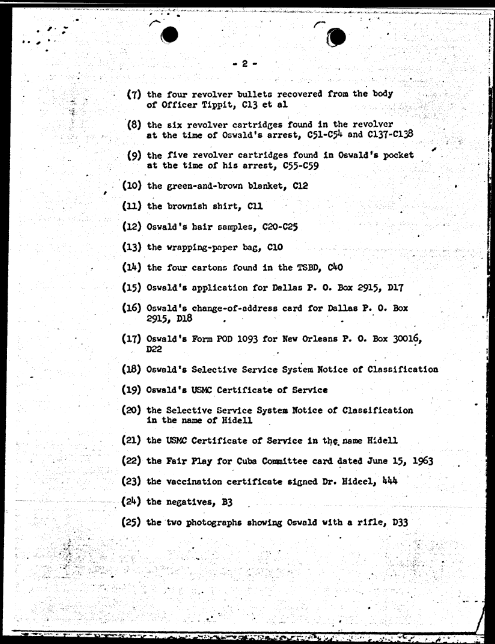

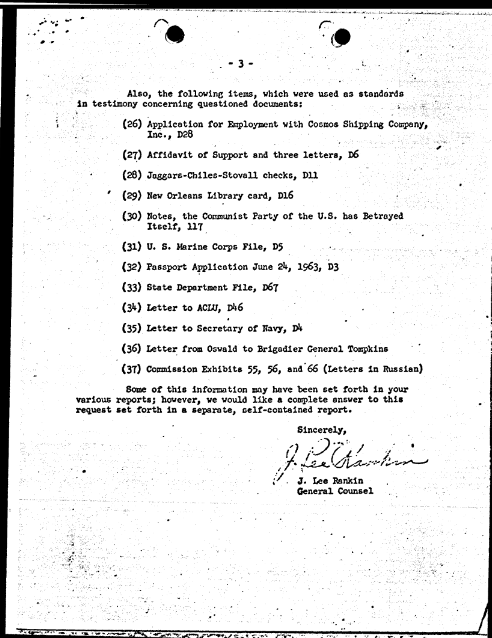

To begin unraveling this mystery, we must first understand the circumstances surrounding the creation of CE2011. On May 20, 1964, Warren Commission Chief Counsel J. Lee Rankin sent a letter to the FBI requesting that the Bureau trace a “chain of possession” for 37 items of physical evidence related to the assassination. However, Rankin specified that the chain only needed to be traced to the first person who could identify the item by inspection. If the person who discovered the item provided a positive identification, that was deemed sufficient.[3]

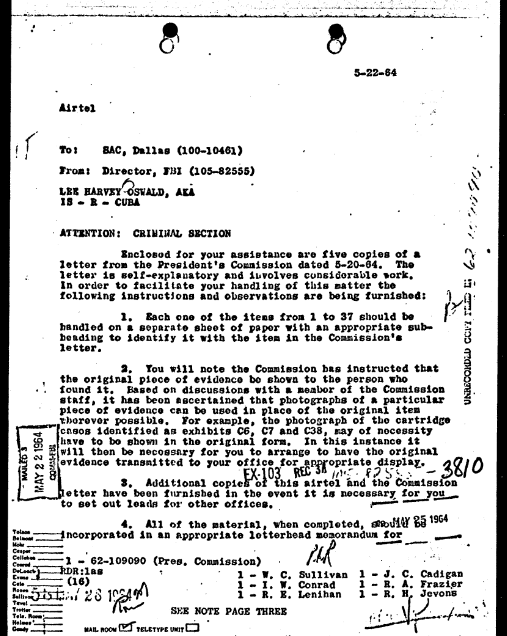

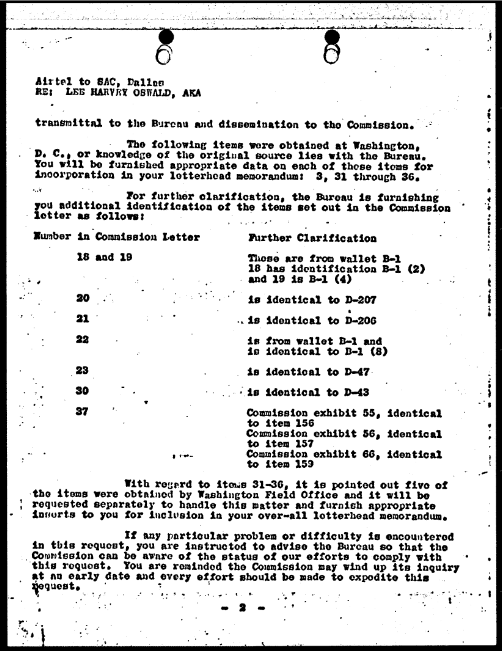

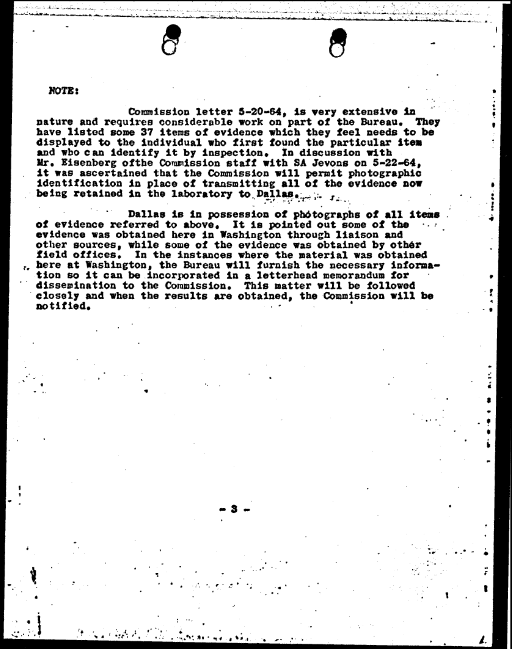

On May 22, 1964, FBI Headquarters forwarded Rankin’s letter to Dallas along with an airtel containing a list of instructions. According to this airtel, Special Agent Jevons of the FBI Lab had spoken to Commission counsel Melvin Eisenberg and convinced him that it would be sufficient to display photographs instead of the original items of evidence “wherever possible”.[4]

The Bureau’s final instruction stated:

All of the material, when completed, should be incorporated in an appropriate letterhead memorandum for transmittal to the Bureau and dissemination to the Commission.

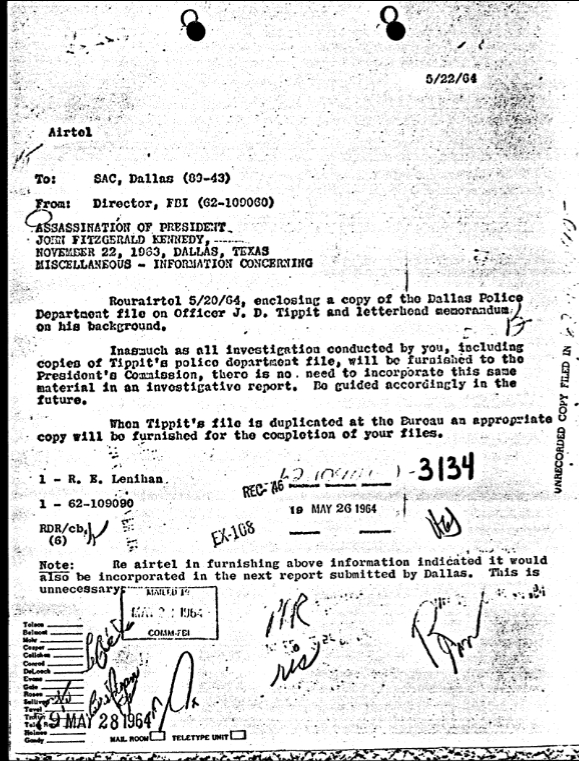

Notably, there was no specific instruction for a separate investigative report. Letterhead memoranda were typically used for quick reporting and dissemination, while formal investigative reports contained the raw data such as 302 reports. This aligns with a separate airtel sent on the same day from FBI Headquarters to Dallas in response to a different request from the Warren Commission.[5]

Inasmuch as all investigation conducted by you…will be furnished to the President’s Commission, there is no need to incorporate this same material in an investigative report. Be guided accordingly in the future. [Emphasis Added]

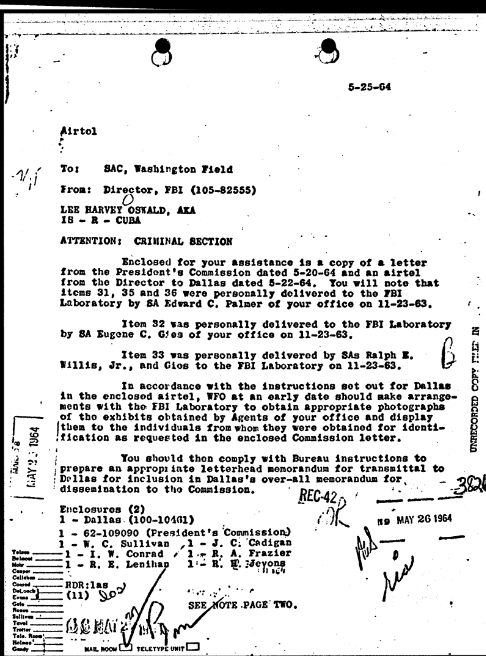

On May 25, 1964, FBI Headquarters forwarded Rankin’s letter and the May 22 Dallas airtel to the Washington Field Office, along with specific instructions on the items to be handled by that office.[6]

On May 27, 1964, Dallas sent a teletype to FBI Headquarters requesting that the laboratory send several original items of physical evidence to Dallas, along with photographs of some of the other items. It appears to have been decided that major items of physical evidence would be displayed in their original form, while questioned documents and minor items such as Oswald’s hair samples would be displayed as photographs. I have not been able to locate any documents on this decision.[7]

On June 2, 1964, FBI Headquarters sent the requested items to Dallas. This was documented in a transmittal airtel and a property invoice sheet.[8][9]

On June 3, 1964, the Washington Field Office sent an airtel to FBI Headquarters and Dallas containing the requested inserts for the final letterhead memorandum. The items handled by Washington included Oswald’s Marine Corps file, a letter from Oswald to Brigadier General Tompkins, Oswald’s letter to the Secretary of the Navy, Oswald’s State Department file, and Oswald’s June 24, 1963, passport application. All of these items were displayed as photographs, not as original evidence.[10]

On June 5, 1964, FBI Headquarters sent an airtel to Dallas containing their inserts for the final letterhead memorandum. The items handled by FBI Headquarters included the rifle bullet fragments discovered in the Presidential limousine and a letter Oswald sent to the ACLU.[11]

This airtel states that Special Agent Orrin Bartlett displayed photographs, rather than the actual bullet fragments, to Navy Corpsman Thomas Mills and Deputy Secret Service Chief Paul Paterni. In the instructions sent to the Washington Field Office on May 25, 1964, FBI Headquarters noted the following:

Item 3 [the fragments] was obtained by SA Orrin Bartlett of liaison and item 34 was obtained by Assistant Director C.A. Evans. They have been advised separately concerning our responsibility in this matter.[12]

Given that the directive to use photographs instead of original evidence “wherever possible” came from FBI Headquarters, it is logical that they instructed their own agent to use photographs in place of the actual fragments.

However, on June 8, 1964, FBI Headquarters sent an airtel to Dallas claiming they had made a mistake. According to this airtel, Bartlett had initially displayed photographs but needed to “obtain” the actual fragments to secure a positive identification from Mills and Paterni.[13]

The interviews in question took place on June 2, 1964. While it is possible that Bartlett displayed photographs, retrieved the fragments from the lab, and reinterviewed the men all on the same day—or that the photograph-based interview occurred earlier—it strains credulity to believe he would omit this detail in his initial report to his superiors. Given that Dallas had requested the original versions of all major items of physical evidence, could the Bureau have been concerned that the only item handled by FBI Headquarters would also be the only one not displayed in its original form? If so, might they have adjusted their reporting to address this inconsistency?

On June 17, 1964, FBI Headquarters sent a radiogram to Dallas inquiring about the status of the Commission’s request and when it would be completed.[14]

Later that same day, Dallas responded with an airtel explaining that they had experienced some delays. According to this airtel, the rifle bullet C1 (CE399) was not positively identified in Dallas. As a result, it would be necessary to send the bullet to Washington to display it to Secret Service Agent Richard Johnsen, Chief of the Secret Service James Rowley, and possibly FBI agents Elmer Lee Todd and Robert Frazier in order to obtain a positive identification.[15]

On June 20, 1964, Dallas sent a follow-up airtel stating that they were returning all the original evidence to the FBI Lab. The airtel instructed the Washington Field Office to obtain the rifle bullet and display it to Richard Johnsen and James Rowley. If they failed to identify it, the bullet was to be shown to Elmer Lee Todd. The airtel also included additional details about the failed identifications in Dallas: neither Darrell Tomlinson nor O.P. Wright could identify the bullet.[16]

Notably, this airtel makes no mention of Tomlinson and Wright’s alleged statements that the bullet resembled the one they found. Given that the report’s focus was on obtaining a full positive identification, the omission of such a detail is not necessarily suspicious. However, it has been suggested that the FBI may have embellished Tomlinson and Wright’s statements to align more closely with the official narrative. This claim stems from an interview Josiah Thompson conducted with Wright in 1966, during which Wright stated that the bullet discovered by Tomlinson did not resemble CE399 and that it had a pointed tip.[17] While it is certainly possible that the FBI adjusted Tomlinson and Wright’s statements to make them more consistent with the official story, without direct evidence of such a revision, this remains speculative.

It has also been alleged that, because this airtel was sent by “SAC Dallas,” and it does not mention Bardwell Odum, Dallas Special Agent in Charge Gordon Shanklin must have conducted the interviews with Tomlinson and Wright.[18] However, this claim is inaccurate. All Bureau communications sent from Dallas were labeled “SAC Dallas” as a matter of standard FBI practice, simply indicating that the communication originated from the Dallas field office or any other field office. Moreover, it is highly unlikely that Shanklin, whose role was primarily administrative, would have been involved in conducting investigative groundwork.

According to an FBI routing slip discovered by John Hunt, the bullet arrived in Washington on June 22, 1964.[19]

That same day, FBI Headquarters sent a letter to J. Lee Rankin stating:

…some delays had been encountered in locating the appropriate individual to identify the specified evidence which are beyond our control.

By this point, the only evidence that remained unidentified was the rifle bullet CE399, so the delays referenced were clearly related to the failure to obtain a positive identification for the bullet in Dallas.[20]

On June 24, 1964, the Washington Field Office sent a teletype to FBI Headquarters and Dallas stating that neither Richard Johnsen nor James Rowley could identify the bullet by inspection. However, Elmer Lee Todd was able to identify the bullet based on the initials he had marked on it before turning it over to the FBI Lab.[21]

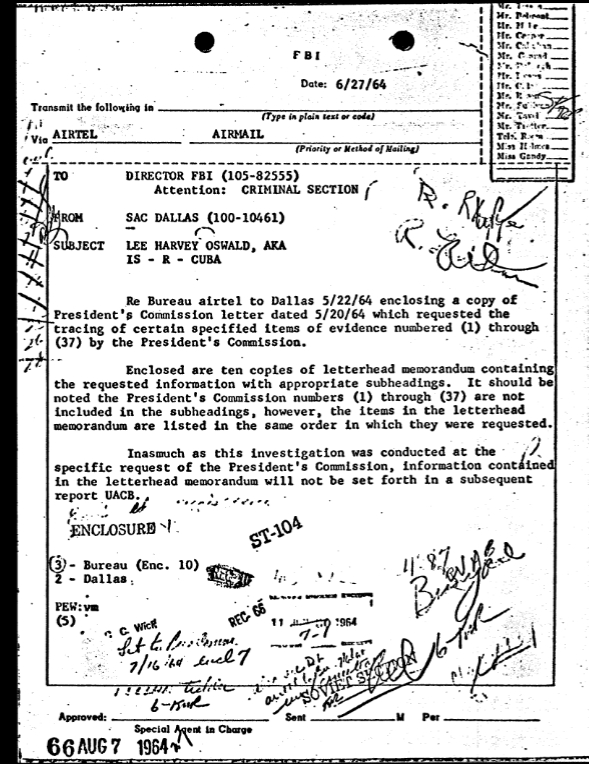

On June 27, 1964, Dallas sent an airtel to FBI Headquarters transmitting the compiled letterhead memorandum for dissemination to the Warren Commission.[22]

This airtel included the line:

Inasmuch as this investigation was conducted at the specific request of the President’s Commission, information contained in the letterhead memorandum will not be set forth in a subsequent report UACB [unless advised to the contrary by the Bureau]

This aligns with the directive Dallas received from FBI Headquarters on May 22, 1964: investigations conducted on behalf of the Warren Commission did not require incorporation into a separate formal report. The absence of 302 reports accompanying CE2011 is no mystery—Dallas had been specifically instructed not to compile formal FBI investigative reports for Warren Commission requests.

Could Bardwell Odum have conducted the interviews with Tomlinson and Wright but failed to recall them 38 years later? Certainly. Odum had no memory of handling CE399 or showing it to anyone at Parkland, but he also did not recall that Dallas had been instructed not to submit formal reports for investigations conducted at the request of the Warren Commission. He wouldn’t have filed a 302 report—because he wasn’t required to.

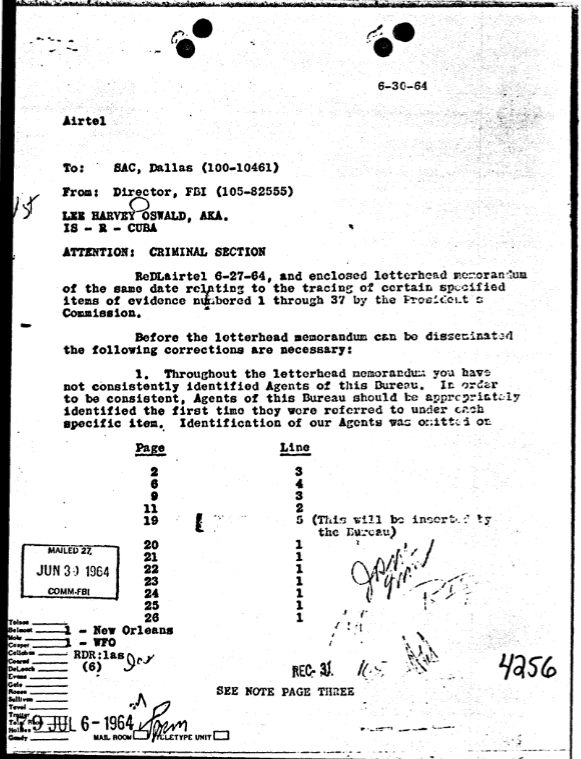

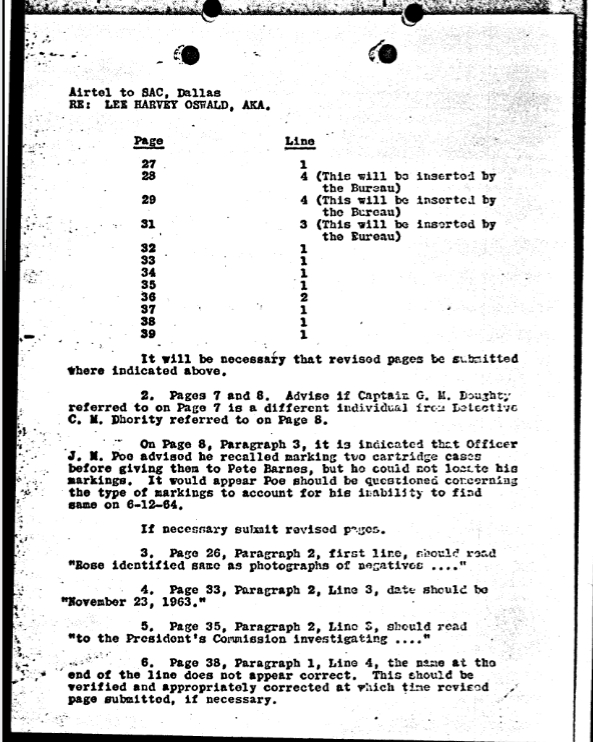

On June 30, 1964, FBI Headquarters sent an airtel to Dallas instructing them to revise the submitted letterhead memorandum. According to this airtel, Dallas had failed to identify the agents who conducted several of the interviews reported in the first draft of CE2011.[23]

The first omission noted is on page 2, line 3, which in the final draft is the first mention of Bardwell Odum in his interview with Tomlinson. Odum’s name also appears on line 11, but without access to the rough draft, it is impossible to determine whether his name was added later. Interestingly, the letterhead memorandum attached to Dallas’ June 27, 1964, airtel in the FBI Oswald HQ File contains the corrected version, which could only have been finalized after June 30.[24] The rough draft of CE2011 would certainly provide valuable insights, but I have not been able to locate it in the JFK files currently available online. It could also potentially shed light on whether Tomlinson and Wright’s statements that CE399 resembled the bullet they found were added later.

Finally, on July 16, 1964, FBI Headquarters transmitted the completed final draft of CE2011 to the Warren Commission.[25]

That concludes the saga of the creation of CE2011. One takeaway from this history is that the absence of 302 reports was neither unique to CE2011 nor inherently suspicious. The FBI had already struggled to keep up with requests from the Warren Commission, and by late May 1964, it anticipated that the Commission would soon be completing its work.[26][27] Given this context, it is understandable that the FBI chose not to allocate additional resources to compile reports for investigations initiated by the Commission rather than the Bureau itself.

However, the elimination of the requirement for formal reporting effectively obscured accountability for the FBI’s actions. Investigations reported solely through letterhead memoranda lack underlying data and, as a result, cannot be independently verified. Considering the FBI’s adversarial relationship with the Warren Commission and its broader pattern of minimizing opportunities for external scrutiny, it is reasonable to suspect that the removal of the reporting requirement served a dual purpose for the Bureau.

This article is only intended to clarify the circumstances surrounding the creation of CE2011, and many questions remain unanswered. One notable gap in the documentary record from Dallas is the period from June 3 – June 17 1964, when investigations were actively underway in the Dallas Field Office. Additional details from this period may exist in the Dallas Oswald Field Office File, but that file is not currently available online. For example, internal Dallas memos might shed light on which agents were assigned to specific interviews, such as Bardwell Odum. In addition, though unlikely, the file may contain the first draft of the letterhead memorandum that was submitted to FBI HQ on June 27. The Dallas Cross Reference Worksheets list a cross reference from Dallas serial 100-10461-6842 to HQ serial 105-82555-4247, the latter of which is the serial of the revised memorandum in the Oswald HQ file.[28]

The date on the letterhead memorandum is listed as July 7, 1964, even though it was submitted with the June 27 airtel. This indicates that the revised version was officially submitted on July 7. Notably, there is no 39-page document dated June 27 listed in the cross-reference sheet, suggesting that the first draft may have been replaced in both the HQ and Dallas files. However, without a direct comparison of the files, this cannot be confirmed.

In conclusion, CE2011 is a fascinating document that provides valuable insight into the FBI’s process for handling investigative requests from the Warren Commission. Understanding the context of its creation helps separate fact from speculation, but many gaps in the historical record remain. If nothing else, I hope this article can serve as a starting point for future research.

References

- FBI Oswald HQ File, Section 180, p. 41 ↩

- Gary Aguilar and Josiah Thompson, “The Magic Bullet: Even More Magical Than We Knew,” History Matters. ↩

- FBI Warren Commission HQ File, Section 17, p.119 ↩

- FBI Oswald HQ File, Section 158, pp. 43-45 ↩

- FBI JFK HQ File, Section 68, p. 54 ↩

- FBI Oswald HQ File, Section 158, pp. 73-74 ↩

- FBI Oswald HQ File, Section 169, p. 54↩

- FBI Oswald HQ File, Section 170, p. 26 ↩

- FBI Oswald HQ File, Section 169, p. 92 ↩

- FBI Oswald HQ File, Section 172, pp. 5-10 ↩

- FBI Oswald HQ File, Section 170, pp. 35-36 ↩

- FBI Oswald HQ File, Section 158, p. 74 ↩

- FBI Oswald HQ File, Section 171, p. 26 ↩

- FBI Oswald HQ File, Section 175, p. 14 ↩

- FBI Oswald HQ File, Section 179, p. 42 ↩

- FBI Oswald HQ File, Section 179, p. 29 ↩

- Aguilar and Thompson, “The Magic Bullet,” History Matters. ↩

- UK Education Forum, Thread: “Is Robert Wagner the new Paul Hoch”, Gary Aguilar, Jan. 9, 2025, 6:40 PM ↩

- Aguilar and Thompson, “The Magic Bullet,” History Matters. ↩

- FBI Oswald HQ File, Section 179, pp. 33-34↩

- FBI Oswald HQ File, Section 179, p. 86 ↩

- FBI Oswald HQ File, Section 180, p. 39 ↩

- FBI Oswald HQ File, Section 181, pp. 7-9 ↩

- FBI Oswald HQ File, Section 180, pp. 41-78 ↩

- FBI Oswald HQ File, Section 190, p. 19 ↩

- FBI Warren Commission HQ File, Section 8, p.287 ↩

- FBI JFK HQ File, Section 72, p.181 ↩

- FBI Dallas 100-10461 Cross Ref (Lee Harvey Oswald), Ser 6329-END, p. 49↩

Leave a comment